The people of the area have lived with the stone as an asset in all ages. The table mountain landscape, with its geology, has provided good conditions for humans to establish themselves in the area. The fertile soil and the flat landscape were optimal for cultivation and large viking farms emerged. The various rocks of the table mountains were soon discovered to be raw materials with many uses.

Megalithic tombs

Gigantic boulders in memory of the dead

Megalithic tombs (from Greek mega = large and lithos = stone) are the oldest manmade structures in Sweden. Two thirds of the country’s megalithic tombs can be found in Falbygden (an area around the city of Falköping in Västergötland), which is also one of northern Europe’s largest concentrations of megalithic tombs from the Neolithic.

The most prominent and monumental structures in the Falbygden landscape are the approximately 250 passage tombs, dating to around 5300–4700 BCE. They are associated with the so-called Funnelbeaker culture and are scattered around most of Falbygden’s limestone plateaus, but somewhat concentrated around Karleby, Falköping, and Gökhem. This type of tomb can also be found in several parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa. The large concentration of passage tombs and cists in Falbygden has traditionally and historically been – and still is – an important characteristic for the area, gaining local, regional, national, and international attention. The vision is to build a centre for the megalithic culture somewhere in Falbygden. Until this becomes reality, Falbygdens Museum functions as a megalithic centre.

Text source: Falbygdens Museum

Tree of Life slabs and staff cross slabs

In a time when Christianity was still young in Sweden, noblemen, kings, and the church fought for power and influence. The power struggle was a game where the players were competitors but also dependent on each other. Among the local elite in the western parts of Götaland, it became a custom to have sandstone grave slabs made with pictures of crosses, Trees of Life, and trailing plant tendrils. They displayed the status of the noblemen and they have come be known as Tree of Life slabs and staff cross slabs.

Christian burial sites, stone churches, and lavish grave monuments show how important the local church and its site were to the social and political ambitions of various groups. The material of the Tree of Life slabs as well as the artful execution of the motifs are evidence that these monuments were expensive investments which only a few could afford. The specific execution of each slab thus became important in the framing of the social status, values, and ideals of the deceased and his family.

It is believed that the Tree of Life slabs were made in a relatively short period of time during the Middle Ages, from the late 12th century to the second half of the 13th century. The staff cross slabs are somewhat older.

There are approximately 530 Tree of Life slabs and staff cross slabs documented in Sweden, and a majority of them can be found in Västergötland, especially in the area around Kinnekulle and south of Lake Vänern. The occasional stone can also be found in the provinces of Värmland, Dalsland, and Bohuslän.

Some of the stones also feature writing, either runic or in the Latin alphabet, which connects the stone to a certain burial. Sometimes we know the people by name, such as Thorsten, Ødgerr, Ragnhild, and Benedictus. The slabs are either single stones or come in pairs with two sets of ornamentation. Some people have interpreted the double stones as marking double graves, for example a married couple, while the single stones mark a single buried person.

The pictures of the Tree of Life and staff crosses are Christian motifs symbolising Christ and everlasting life after the Resurrection. These motifs can be found in religious art in large parts of Europe and the Middle East, but the individual pictures and the way they were executed in these sandstone grave slabs are also an expression of something personal and specific. In the areas south of Lake Vänern, there emerged a grave custom based in local traditions and ideas while also being a part of a Christian and ecclesiastical all-European context of ideas. The motifs can be seen as a result of encounters between people from different parts of the world and intersecting thoughts and ideas. The execution of the stone slabs and their motifs show that the people of the 13th century, just like today, in many ways were part of a world that was much larger than the place in which they lived and died.

Text source: Vänermuseet

Stone churches

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Västergötland saw its first boom in stone buildings since the megaliths of the Stone Age. Several hundred stone churches were constructed in a short time. Master builders and masons arrived from Germany and England to teach the people of Västergötland how to work the sandstone and limestone found in the table mountains into building stones and sculptures.

The first churches were built of raw limestone and later of sandstone, carefully hewed into square blocks. Wealthy aristocratic families probably funded most of the projects. The churches became a way to both serve God and express the family’s wealth and status. The richest contractors could afford porches adorned with sculptures, and even a church tower.

The largest mediaeval construction projects in the table mountain region were the cathedral in Skara and the abbeys in Gudhem and Varnhem. The Romanesque cathedral, richly decorated with stone sculptures, was finished in 1150. Most of the sandstone for the cathedral was mined at Kinnekulle and Billingen, for example in quarries at Gössäter, Broddetorp, and Gudhem.

Västergötland’s second boom in stone churches came in the 19th century, as over one hundred churches were constructed between 1850 and 1890 on and around the Västgöta plain. Just as in mediaeval times, there were master builders specialising in churches. Building a church was a joint effort by the parish farmers, and there was surely a certain amount of competition involved, as the farmers tried to outdo the neighbouring parishes.

The role of the table mountain landscape in the history of Sweden

A little over a thousand year ago, the Vikings ruled the North. It was the Viking Age, but people in Västergötland were already Christians. We know this thanks to archaeologists from Västergötlands Museum who have excavated Christian graves in Varnhem. And evidence suggest that it was a woman, Kata, who ordered the construction of the first Swedish stone church, at Varnhem. She was also the head of the nearby farming estate.

Exciting discovery at Kata gård

Kata Farm includes the remains of both a large farmstead and a Christian church in Varnhem, at the western slopes of the table mountain Billingen. The remains date to the time before Cistercian monks established a monastery here in the 12th century. But people have lived here for thousands of years: already in the 1870s and 1880s, remains were discovered which could be dated to the second century AD. The name Kata Farm, however, is a recent one based on the presumed owner of the farm in the early 11th century, Kata. Kata’s lavish grave, sealed with an engraved runestone, has been excavated. Kata was between 30 and 35 years of age when she died, 160 centimetres in height and of slender build. Remnants of the clothes she was buried in have been found. Her teeth were in very good condition, without any signs of caries, infections, or heavy wear and the skeleton shows no signs of her having performed heavy manual labour. Her grave is the most lavish on the site and located right next to the church foundations. The conclusion is thus that she was a very influential woman who probably owned the farming estate in Varnhem together with her husband Kättil, a man which was discovered in another grave on the site from the same time. The inscription on Kata’s grave reads: Kättil made this stone after Kata his wife sister of Torgil.

Early Christianisation

The archaeological excavations in Varnhem show that Västergötland was Christianised no later than the 10th century, i.e. earlier than the rest of Sweden. In the thousands of graves surrounding the old stone church, people have been buried without first being cremated (as was the earlier custom), and with their heads to the east and their feet to the west according to Christian tradition. The graves are also sorted after social status and sex: women were buried north of the church, men to the south. The owner families were placed closest to the church, whilst farmers were placed a little further out and thralls on the outskirts of the cemetery. There are no traces of coffins in the poorer graves.

The oldest discovered graves have been dated to the first half of the 10th century, and the church crypt might be the oldest preserved room in Sweden. The walls of the crypt measure two metres in height and are made of locally mined limestone. They were probably constructed around the mid-11th century. During the 12th century, stone churches proliferated in the area. The many stone churches can be interpreted as evidence of wealth and surplus from farming and cattle, which in turn came from the rich and fertile soil in the table mountains region.

Text source: Västergötlands Museum et al.

Industrial history

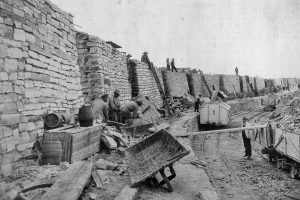

Platåbergen has a history of large-scale stone industry spanning thousands of years. With Christianity followed the art of stonemasonry and every century thereafter show examples of how stone from the mountains’ different layers were used in churches, graves, houses, cattle sheds, bridges, and many other constructions. Along the mountain sides, rows of quarries, scrap stone piles, kiln remains, and red ash heaps are a constant reminder of the tireless work to create something lasting. But sometimes there is hardly a trace of what once was.

Master masons showed the way

Experienced master masons from England and Germany showed the people of Västergötland how the sandstone and limestone from the mountains could be shaped into walls, arches, ornaments, and figures. Kinnekulle became an early centre for the stone industry since it had the best stone. Mortar was needed for the buildings, and it was often made on-site from limestone in wood-fired kilns. During the early 19th century, alum shale began to be used as fuel in the kilns to conserve wood. The industry also included the cutting of millstones, and so-called Lugnås millstones became a widely known term. The five alum works operating in the table mountains region during the 18th and 19th centuries formed an early large-scale industry. Nowhere else were alum works as densely placed as here.

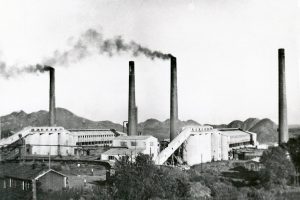

With machines and railroads

When the industrialised society began to form in the late 19th century, the demand for what the table mountains could yield increased – stones for buildings, agricultural lime, and the new material known as cement. Machines, new methods, and a fine grid of railroads made it possible to meet the demands. Mechanised quarries delivered processed limestone to the houses and institutional buildings of the growing cities. The burning of limestone was developed into an important industry, focussing especially on agricultural lime. At its peak, some sixty lime works in the table mountains region answered for more than half of the country’s demand. Cement production meant large and very expensive plants, yet two factories were constructed in the area; one in Hällekis and one in Skövde.

A job for men

Up until the industrialisation, burning of limestone and quarrying were seasonal work that people engaged in alongside farming. The modernised industry featuring large-scale lime works, mechanised quarries, and cement factories became a leading industry in the table mountains region, operating all year round and offering paid employment. The work was heavy: well into the 20th century all stone was lifted by hand and on backs. It was a job for men, while the women took care of things at home. In this age, it was not uncommon for strong boys to begin at the works even before they finished school. Today, the largest of the works in the region is managed by a woman.

Versatile rock

Alum shale has been mined not only by the lime and alum works, but also for the extraction of oil, radium, and uranium. Shale oil was an early alternative to regular petroleum and trials to extract oil from alum shale were made at Kinnekulle from the 1880s until World War II. The government then built a large refinery at Kinnekulle to secure the navy’s demands for oil. And when radium became a weapon in the fight against cancer in the early 20th century, a grand but utterly unsuccessful attempt was made to extract alum shale at Billingen. The most spectacular attempt to mine alum shale, however, was the Ranstad works near Billingen. The government wanted to secure a supply of uranium for the Swedish nuclear weapons and nuclear power programmes. The uranium deposit at Ranstad was described as one of the largest in the world but the short-lived production covered only a fraction of the demand – while the negative environmental impact was huge.

“Folkhemmet”, the People’s Home

Folkhemmet was a political concept, advocated by the Swedish Social Democratic Party between 1932 and 1976, that envisioned the entire society as one big family. This concept encompassed all aspects of society and politics, including housing politics. When the vision was set to become reality, a lot of the building material came from Platåbergen: aerated concrete, mineral wool, and cement. Aerated concrete was produced in factories in Skövde and in the Falbygden area under brands such as Durox and Ytong. All the factories produced so-called “blue concrete” using alum shale and limestone as raw materials. However, when the blue concrete proved to be a health hazard because it contained radium, production was shut down. For many years, Rockwool had a factory in Skövde where mineral wool was manufactured from diabase. The cement factories in Skövde and Hällekis also had full schedules to meet the demands for the massive public housing project known as the Million Programme.

An important resource

The mountains are still an important resource for the people in the table mountains region. Billingen is a source of limestone for the cement factory in Skövde as well as a source of diabase for the mineral wool factory in Hällekis. These two factories are the only two stone industries of significance left in the region. In several places in the mountains, the bedrock is mined to be used as ballast in asphalt and concrete. Limestone is also mined for agricultural purposes. Stone as a natural resource will be needed for future projects as well, and it is important to mine it as sustainable as possible.

Text: Eric Julihn